Implications of the emergence and spread of the SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern BA.4 and BA.5 for the EU/EEA

Most European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) countries have detected low proportions of the SARS-CoV-2 variants BA.4 and BA.5, however many have seen an increase in recent weeks. In Portugal, BA.5 has become the dominant SARS-CoV-2 variant and the increasing proportions of BA.5 have been accompanied by a surge in COVID-19 cases. The growth advantage reported for BA.4 and BA.5 suggest that these variants will become dominant throughout the EU/EEA, probably resulting in an increase in COVID-19 cases in coming weeks.

The extent of the increase in COVID-19 cases will depend on various factors, including immune protection against infection influenced by the timing and coverage of COVID-19 vaccination regimes, and the extent, timing and variant landscape of previous SARS-CoV-2 pandemic waves. Based on limited data, there is no evidence of BA.4 and BA.5 being associated with increased infection severity compared to the circulating variants BA.1 and BA.2. However, as in previous waves, an increase in COVID-19 cases overall can result in an increase in hospitalisations, ICU admissions and deaths.

Countries should remain vigilant for signals of BA.4 and BA.5 emergence and spread; maintain sensitive and representative testing and genomic surveillance with timely sequence reporting, and strengthen sentinel surveillance systems (primary care ILI/ARI and SARI). Countries should continue to monitor COVID-19 case rates - especially in people aged 65 and older - and severity indicators such as hospitalisations, ICU admissions, ICU occupancy and death.

Improving COVID-19 vaccine uptake of the primary course and first booster dose in populations who are yet to receive them remains a priority. It is expected that additional booster doses will be needed for those groups most at risk of severe disease, in anticipation of future waves.

Event background

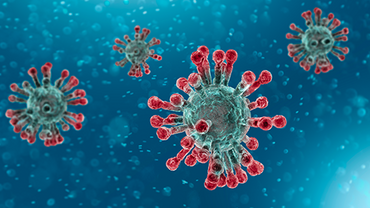

The SARS-CoV-2 variants BA.4 and BA.5 were first detected in South Africa in January and February 2022, respectively. They became the dominant variants in that country in May 2022 [1] and a parallel increasing trend in epidemiological indicators, such as case notification rates and test positivity rates [2], suggested that these two variants were responsible for the surge in cases observed in South Africa in April−May 2022. As of 12 May 2022, ECDC reclassified Omicron sub-lineages BA.4 and BA.5 from variants of interest to variants of concern [3].

BA.4 and BA.5 are two sub-lineages of the Omicron clade (B.1.1.529). They share the same mutation profile in the spike gene, while they have different sets of mutations in their remaining genome. The defining mutations in the spike protein of BA.4 and BA.5 compared to BA.2 include Δ69-70, L452R, F486V and R493Q (reversion). Given the current epidemiological background where BA.2 is the dominant variant in the EU/EEA, laboratories can use the presence of the spike changes L452R or F486V or S-gene target failure [4] as a pre-screening for the variants. To be able to differentiate between BA.4 and BA.5, assays targeting discordant parts outside of the spike gene or whole genome sequencing (WGS) are required. Since BA.4 and BA.5 only emerged recently, it has not yet been possible to include the variants in a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) evaluation study.

There is currently no indication of any change in severity for BA.4 or BA.5 compared to previous Omicron lineages. Severity indicators in Portugal (hospitalisation, ICU admissions and deaths) as of 1 June are below the levels reached in the previous Omicron peak, however, week-on-week increases continue to be observed. Over the past six weeks, both hospitalisations and ICU admission increases have mainly been among those aged 60 years and above [5].

The current growth advantage for the BA.4 and BA.5 variants of concern (mainly observed in South Africa [4] and Portugal [6]) compared to the dominant variant BA.2, is probably due to their ability to evade immune protection against infection induced by prior infection and/or vaccination, particularly if this has waned over time. Based on preliminary in-vitro data from preprints, BA.4 and BA.5 are antigenically distant from the ancestral virus [7,8] and, compared to BA.1 and BA.2, they are less efficiently neutralised by sera from individuals vaccinated with three doses of COVID-19 vaccine (Vaxzevria or Comirnaty), or by sera from BA.1 vaccine breakthrough infections [8,9]. In addition, there has been an increased rate of re-infection in Portugal [5]. Overall, this raises concerns about more frequent BA.4/BA.5 vaccine breakthrough infections than for BA.1/BA.2, and for Omicron reinfections. Nevertheless, as of the end of week 22, 2022, overall transmission continues to decline in most EU/EEA countries, as shown by both overall case notification rates and case rates among people aged 65 years and above [10].

More evidence is needed to elucidate the efficiency of monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against the BA.4 and BA.5 variants, but evidence so far suggests that BA.4 and BA.5 have shown a reduced or broadly similar pattern of mAb sensitivity to that of BA.2 [7,11,12].

At present, there are no data available on vaccine effectiveness against different clinical outcomes for Omicron sub-lineages BA.4 and BA.5. Data on vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron variants BA.1 and BA.2 are described in a recently published ECDC technical report on the second mRNA COVID-19 vaccine booster dose [13].

BA.4 and BA.5 in the EU/EEA: update as of 13 June 2022

BA.4 and BA.5 were first detected in the EU/EEA in March 2022. Portugal was the first country in the EU/EEA to observe a significant increase in cases and in the proportion of one of these two variants (BA.5). As of 30 May 2022, BA.5 is the dominant SARS-CoV-2 variant in Portugal, with an estimated proportion of around 87% [6,14]. Between week 19 and 20, 2022, case numbers in Portugal declined and became stable, indicating that the peak of a BA.5 wave in Portugal may have been reached. In recent weeks (week 17−21 of 2022), an increase in the proportion of BA.4 and BA.5 infections was observed in many EU/EEA countries including Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Spain and Sweden [15,16].

In particular, in Belgium BA.5 reached an estimated proportion of 19% and BA.4 accounted for 7.5% of the sequenced genomes during weeks 21−22. In Spain, BA.4 and BA.5 accounted for more than 10% of the samples analysed by variant-specific PCR in 10 autonomous communities during weeks 21−22, with a wide variation between the communities. In the Netherlands, BA.5 reached a proportion of 8% in week 20, while BA.4 was detected in a proportion close to 5%.

The growth advantage reported for BA.4 and BA.5 suggest that these variants will become dominant in the whole EU/EEA, probably resulting in an increase in COVID-19 cases in the coming weeks. The extent of the increase will depend on various factors, including immune protection against infection influenced by the timing and coverage of COVID-19 vaccination regimes and the extent, timing and variant landscape of previous SARS-CoV-2 pandemic waves. Based on limited data, there is no evidence of BA.4 and BA.5 being associated with increased infection severity compared to the circulating variants BA.1 and BA.2. However, as in previous waves, an increase in COVID-19 cases can result in a rise in hospitalisations, ICU admissions and deaths.

Monitoring and reporting

ECDC encourages countries to remain vigilant for signals of BA.4 and BA.5 emergence. Sensitive and representative testing policies and genomic surveillance are required to accurately determine the extent to which these variants may contribute to any observed increases in severe outcomes in the population (e.g. increases in hospital or ICU admissions).

Countries should therefore strengthen sentinel systems (primary care ILI/ARI and SARI) and continue to collect data on laboratory-confirmed cases (from non-sentinel sites) and on hospitalisations/ICU admissions and hospital bed occupancy [17]. Countries should remain vigilant and scale up testing and sequencing if required. Countries should continue to sequence positive specimens and share sequence data in a timely manner [18,19]. SARS-CoV-2 consensus sequences should be deposited in the GISAID database and, if available, raw data of SARS-CoV-2 sequences should be deposited in the COVID-19 data portal through the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) [20]. If possible, antigenic characterisation should be undertaken as this will contribute to an understanding of the properties of these variants and specimens/isolates could also be shared for characterisation with the WHO reference laboratories [21].

Minimum metadata should be reported to TESSy case-based record type NCOV or in aggregated form to NCOVVariant and, if possible, GISAID accession numbers of sequenced cases should be reported. ECDC has invited nominated users of countries to use the EpiPulse event on BA.4 and BA.5 to informally discuss and share information on these two variants, specifically on virus characterisation and evidence on changes in disease severity, virus transmissibility, immune evasion and effects on diagnostics and therapeutics.

Vaccination

Improving COVID-19 vaccine uptake of the primary course and first booster dose in populations remains a priority for all age groups in order to reduce the COVID-19 hospitalisation and death burden. Detailed information on COVID-19 vaccine doses administered and vaccine uptake rates are reported on the ECDC Vaccine Tracker [22].

Depending on the evolving epidemiology, data on vaccine effectiveness over time, and other factors such as seasonality, it will be necessary to re-assess recommendations on timing and the populations that may benefit from additional booster doses.

The public health benefit of administering a second mRNA COVID-19 booster dose was recently assessed by ECDC to be clearest in those aged 80 years and above and immediate administration of a second booster dose in this population was found to be optimal in situations where viral circulation was high or increasing. Mathematical modelling also suggests that a second booster roll-out including those aged 60−79 years who are immunocompetent in the EU/EEA will probably be beneficial in terms of averted deaths, although the best timing for the roll-out is uncertain and will depend on future waves [13].

Additional booster doses in anticipation of future waves, or in advance of the autumn/winter season, are expected to be needed for rapid deployment in those groups most at risk of severe disease (e.g. adults aged 60 years and above and medically vulnerable populations). These additional doses will have the greatest impact if administered closer to expected periods of increased viral circulation, but before it reaches high levels.