Variant Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease in donors of blood and plasma having temporarily resided in or visited the United Kingdom

Since the previous risk assessment on the risk of vCJD disease transmission via blood and plasmaderived medicinal products (PDMP) manufactured from donations obtained in the UK (August 2021), no new cases of transfusion-transmitted vCJD or cases associated with dietary exposure have been reported in the EU/EEA or the rest of the world. The risk of vCJD transmission posed by donors having temporarily resided in or visited the United Kingdom should be balanced against the local blood and plasma supply needs, and the expected benefit from removing the restriction.

Executive summary

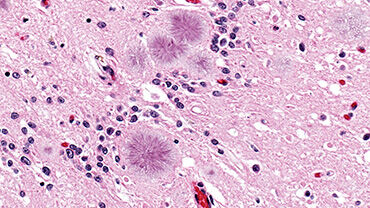

Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) is a rare neurodegenerative zoonotic disease, classified as a prion disease or transmissible spongiform encephalopathy, characterised by progressive neurodegeneration ultimately leading to the death of the host. As there is a risk of secondary infection through transfusion, some countries have imposed deferrals for blood donors considered to have had a risk of exposure due to prior residency in the United Kingdom (UK).

In 2022, both the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) removed the restrictions on blood donors who had previously spent time in the UK. In the light of these decisions, ECDC has been requested to consider whether the current deferral in the EU for prospective donors of blood and plasma after prior temporary residency or visit to the UK is still relevant and justified by scientific evidence, or could be removed.

Since the risk assessment published by ECDC on the risk of vCJD disease transmission via blood and plasma-derived medicinal products (PDMP) manufactured from donations obtained in the UK (August 2021), no new cases of transfusion-transmitted vCJD or cases associated with dietary exposure have been reported in the European Union and European Economic Area (EU/EEA), or in the rest of the world. As such, the overall risk assessment for vCJD transmission through blood remains unchanged: in the absence of a reliable diagnostic blood test, the risk of vCJD infection transmission through blood components remains uncertain. The decisions taken by the US and Australian regulators were based on the results of mathematical models. The modelling estimated the increased risk of transfusion-transmitted vCJD after the removal of restrictions as very low or negligible, with no or a very low increase in the projected number of vCJD cases. This risk was considered acceptable by the US and Australian regulators, supporting the decision to remove the restrictions. Although they are robust to sensitivity analyses, the number of projected cases of transmission resulting from these models are strongly influenced by the assumptions on the prevalence of carriers of infectious vCJD agent in the UK, and this is an estimate for which there remains much uncertainty. In order to determine whether current restrictions for prospective donors of blood and plasma due to temporary residency or having visited the UK are still justified, EU/EEA countries could consider assessing the impact of these restrictions on the local increased risk of transmission of vCJD through blood by using similar mathematical models. This risk could then be balanced against the blood and plasma supply needs in the country, and the expected benefit from removing the restriction. In the future, ECDC intends to support countries with decision-making through the newly-created SoHO-network which will also be a platform for EU/EEA country exchange on national risk assessments, risk models, and decision-making on the deferral of donors due to the risk of vCJD transmission.